Can I do your (org) chart?

Posted in Campfire Stories, The Art of Programming on March 1st, 2006I’ve been talking to lots of firms lately and I’m starting to believe that you can tell whether a company is serious about software and technology development by merely

1. Examining their org chart.

2. Asking them how willing they might be to changing their organization, especially if their org chart sucks.

This will have different ramifications depending on whether you want to join one of these companies as an employee or work with one of these companies as a consultant or consulting firm. In general, if you work at a company that fails the tests above (Sucks, refuses to change, respectively) you are probably Screwed (See especially Screwedness type #5).

If you want to consult at a company that fails the tests above, this company could be a gold mine. Assuming you are skilled and competent, they will need you just to be able to tie their own shoes. And they will never evolve into a company that does NOT need you. Ditto if you’re part of a consulting firm.

Let’s look at some concrete examples.

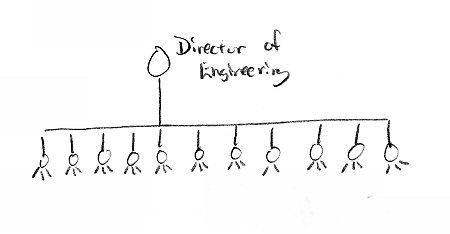

The Flat Model

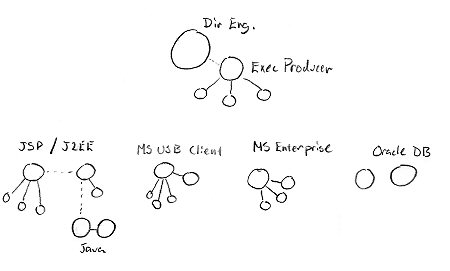

This org chart is really popular these days. The little “legs” below the circles represent more direct reports so this plan involves 11 Lead developers with a total team size of 40-50.

This is the “flat” model. A.k.a. “we don’t need no stinking middle managers.” Here “middle managers” means anyone more senior than the many small team leads yet below the Director.

This org chart is effective if the development pace will be glacial or non-existent.

The other way this chart works is if each little project is completely un-coupled from all the other projects.

Little decoupled projects or slow maintenance mode == not a chart that says the company is serious about development.

Why? Because there’s insufficient cross team communication bandwidth to clear coordination problems. No “super leads”, no program managers.

When people are trying to build big projects fast, you run into situations where you need something from your neighbor. Something they had not planned on (because you had not planned on it). This means the leads having to stop and negotiate the interface issue.

A good middle manager delivers value by doing NOTHING but anticipating and clearing these team-to-team issues – keeping things moving forward. In the flat model there are no middle manager so this clearly assumes that the Director is doing all of it.

Having been the Director in a plan like this, I can assure you that once things get big and fast it is not possible for the director to have clear knowledge of what, exactly, is going on in all those teams.

It becomes management by fire control. The team on fire with the most problems gets the attention. Everyone else does without.

How do you solve a flat model?

Reorganize and create de-facto middle managers.

I was placed in charge of a project with a total team size of 105 developers, project managers, and graphics people spread across three companies and working at three different locations (LeapFrog Enterprises, Q1-2001).

I was successful only because management had flipped the bozo bit on the entire team. I could change anything I wanted — I could fire anyone I wanted to. The one person who needed firing was gone (the person who set up this monstrosity).

The “fix” is a post in and of itself but in summary: All I had to do was break the flat model.

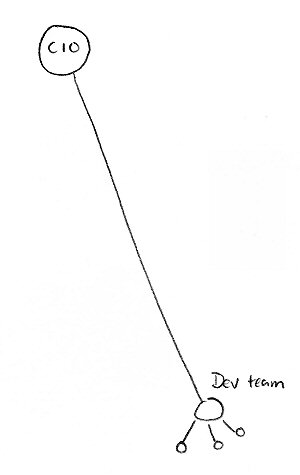

The Silo

Here’s another org chart that screams: we are not building anything here.

This is a real situation. Here’s a senior developer with a small team reporting to a CIO. If the company is teeny tiny this doesn’t look that weird. But this is a real company that has over 800 employees and does over $650 million in sales each year. Think the CIO spends lots of quality time guiding that dev team?

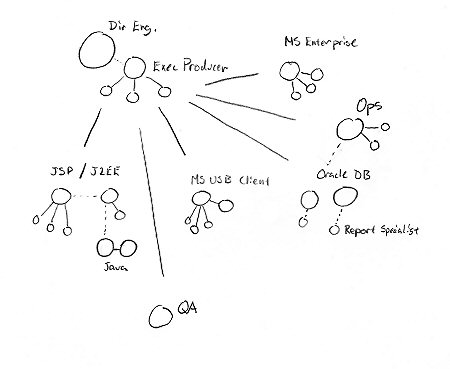

I gave an example earlier of the massive train wreck I had to run. Once the dust settled (we shipped on time) and the consultants went home, I was left with a team that looked like:

This sort of worked. By the coy way I’ve drawn this I’ve carefully hidden that this is a big fat FLAT model. What problems did I have? Give you one guess:

It was impossible for me to really manage what was happening within and between all the teams because there is insufficient communication bandwidth available to clear coordination problems.

At this time we were no longer in a growth mode. I changed the chart by giving things away. I worked to have the lead of the Ops group promoted to be a peer Director of Operations and gave him the portion of the DB team that was really operations of the production database systems. He also got reporting and the QA group.

I kept the more senior development DBAs. This is what my group looked like after:

The cool thing is that it made my team much more focused on development and that’s what I enjoy the most anyway.

If this team had ever needed to grow (it never did) the way to do that would have been to promote one of the leads into a middle management role.